When the Engine Stalls: Cracks in the Auto Industry

From subprime delinquencies to falling used-car values, stress is spreading across the auto sector, a warning sign for the broader consumer credit cycle.

Last week, I wrote about cracks forming in the credit boom, a reminder that in every late-cycle environment, leverage tends to reveal its weak links first. I discussed how the TriColor and First Brands Group bankruptcies appear relatively idiosyncratic, with fraud playing a key role in their downfalls. But it’s no coincidence that both troubled companies were in the auto sector, one being a parts supplier, the other a subprime lender. The auto industry sits at the intersection of consumer spending, industrial production, and credit markets, and right now, all three are flashing warning signs.

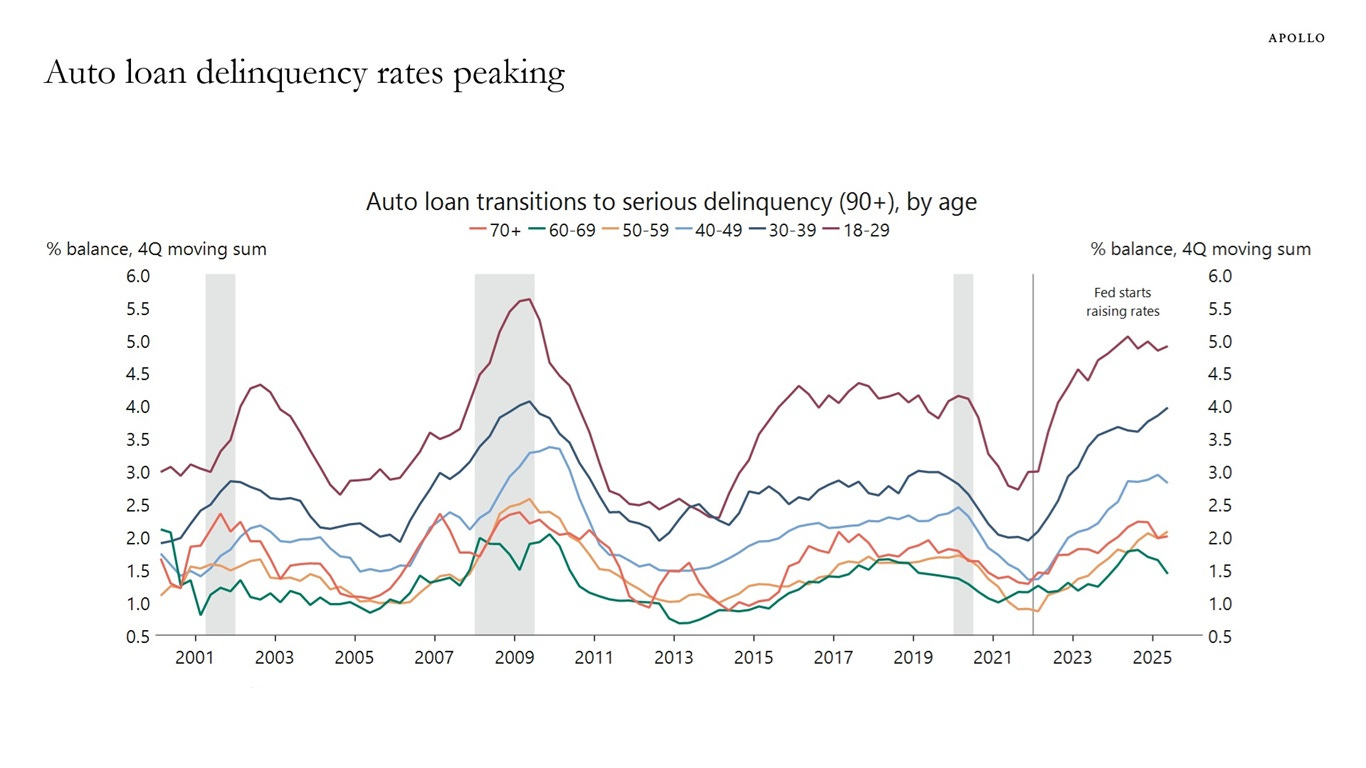

Auto loans serve as a sort of canary in the coal mine for household credit stress. They’re smaller, shorter-term, and more income-sensitive than mortgages, making them one of the first places strain tends to appear when borrowing costs rise. And strain is exactly what we’re seeing: subprime auto delinquencies have surged to their highest levels since the financial crisis, while used-car values, the collateral behind much of this lending, continue to fall.

The result is a slow-motion squeeze across the auto ecosystem. Consumers are increasingly unable to keep up with payments, lenders are facing higher losses, and securitizations are now filled with riskier loans. The pressure is building across balance sheets, and it’s starting to test the resilience of the broader credit cycle.

Auto Lending

To understand how these pressures are building, it’s worth looking at the auto credit market itself.

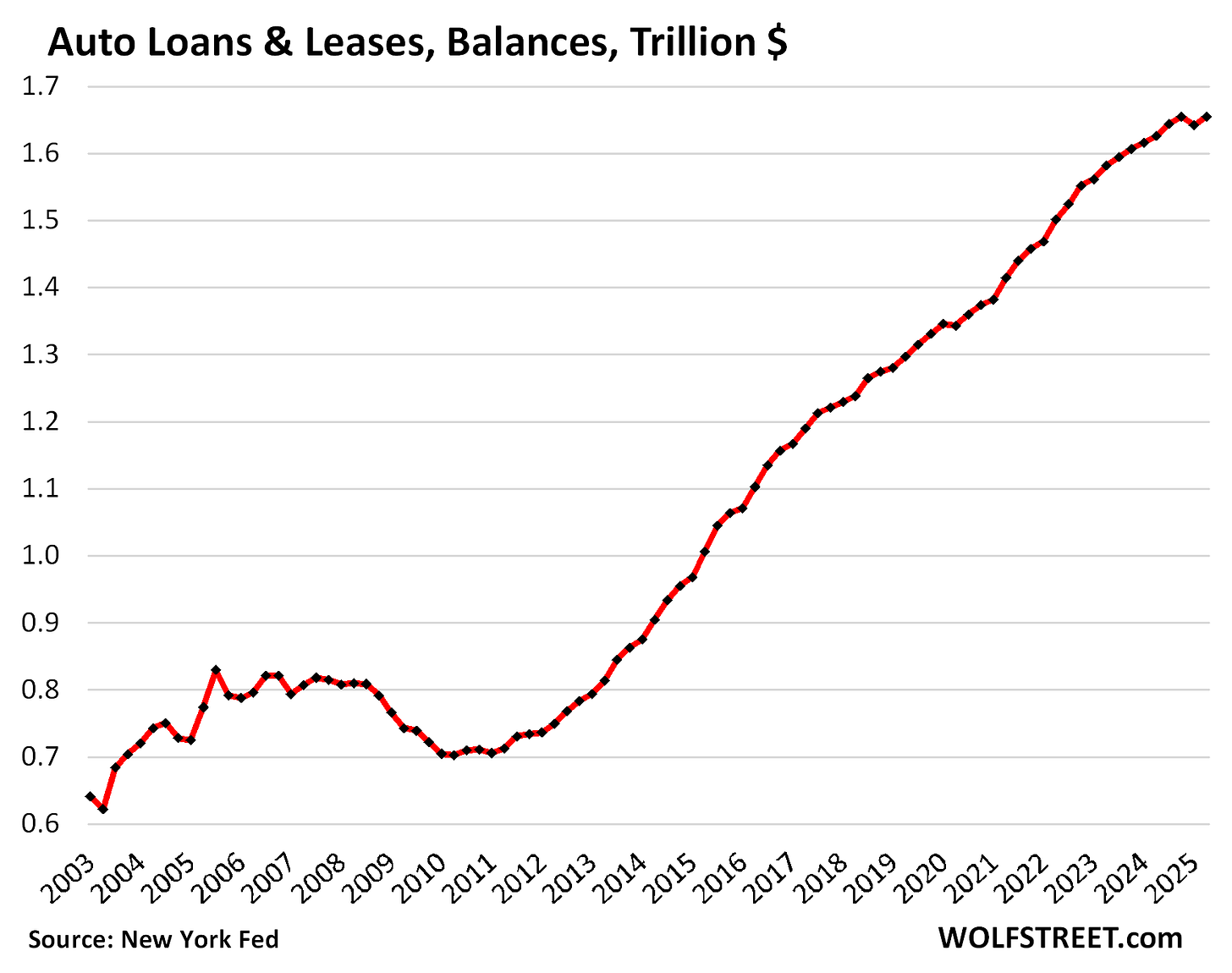

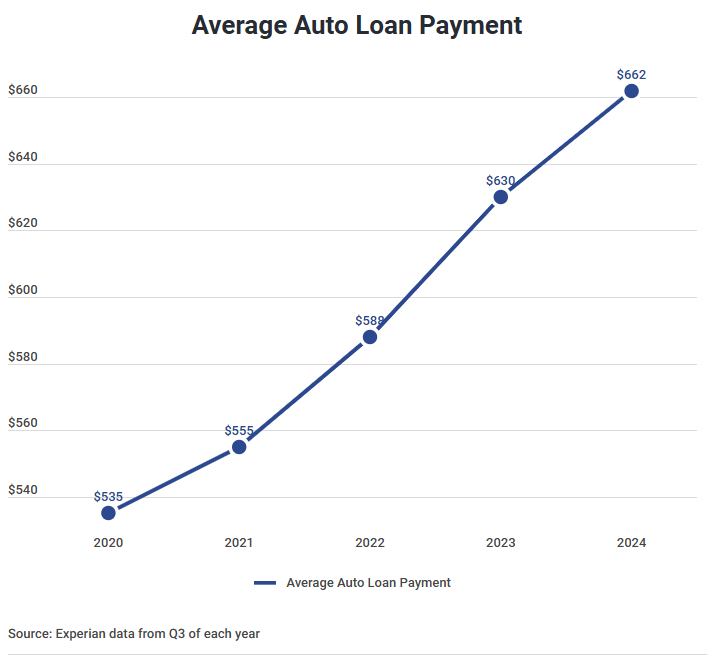

Total balances of auto loans and leases for new and used vehicles have reached nearly $1.7 trillion in the U.S., a record high. Auto debt has become a meaningful burden on household finances. According to Experian, the average monthly auto loan payment has climbed to $662. With median household income at roughly $83,700 in 2024, that means the average household is spending about 10% of its gross income on car payments, an unusually high share for a depreciating asset.

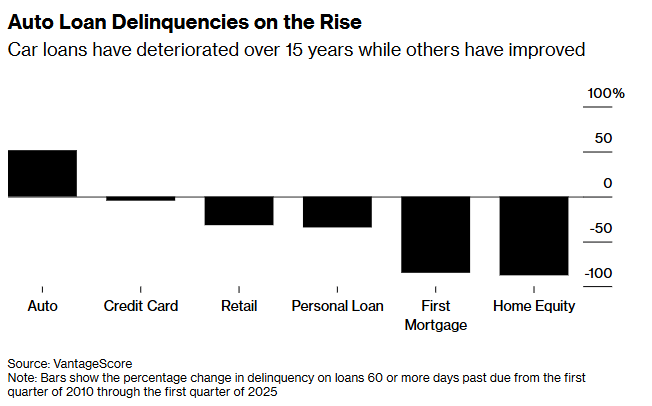

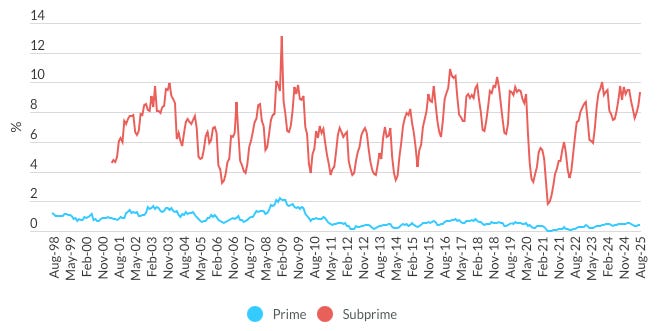

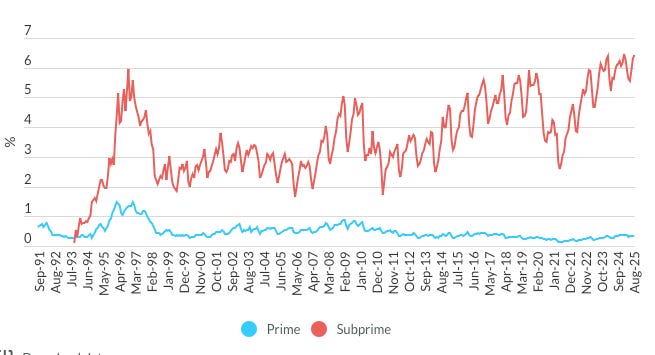

Delinquencies on subprime auto loans have hit their highest levels since the Great Recession. From the first quarter of 2010 through the first quarter of 2025, delinquencies, defined as loans 60 days or more past due, have surged over 50%. Over the same period, the opposite trend is visible in credit cards, personal loans, and other forms of consumer credit.

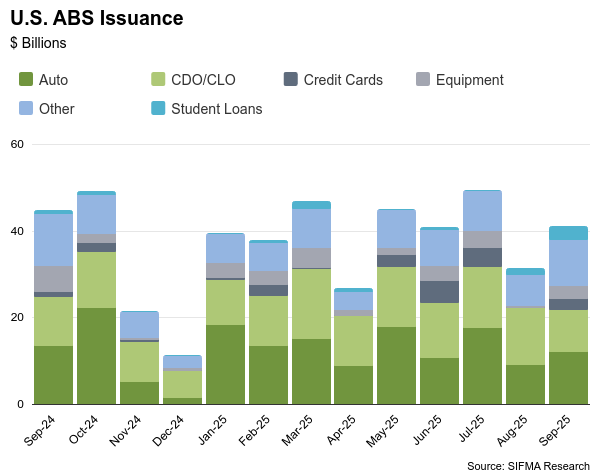

If these rising delinquencies turn into a wave of defaults, they could spill over to investors in asset-backed securities (ABS), where auto loans make up a meaningful slice of underlying collateral. TriColor, for instance, was a major originator of subprime loans that were securitized into ABS deals.

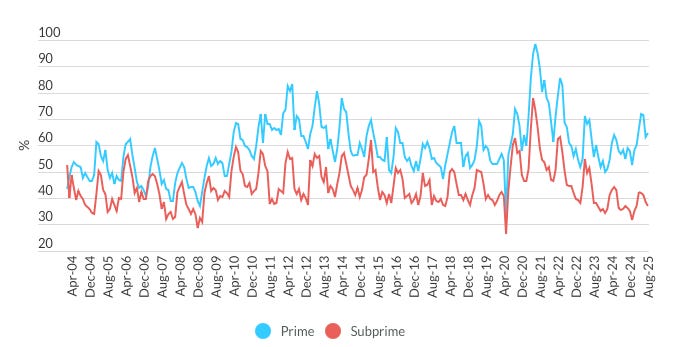

To illustrate the current status of the auto loans collateralized in ABS portfolios, I will let the following charts mostly speak for themselves.

Subprime Annualized Net Losses are raising:

Subprime delinquencies are raising (higher than during the GFC):

Subprime recovery rates are falling and diverging from prime recoveries:

Depreciating Collateral

The core problem with auto lending, compared with mortgages, is that the underlying collateral loses value almost immediately. Unless you’re financing Ferraris, most vehicles, the Hondas and Fords, depreciate the second you drive them off the lot.

That creates a vicious cycle when borrowers fall behind. As car values decline faster than loan balances, negative equity builds, making it easier to walk away from the loan altogether.

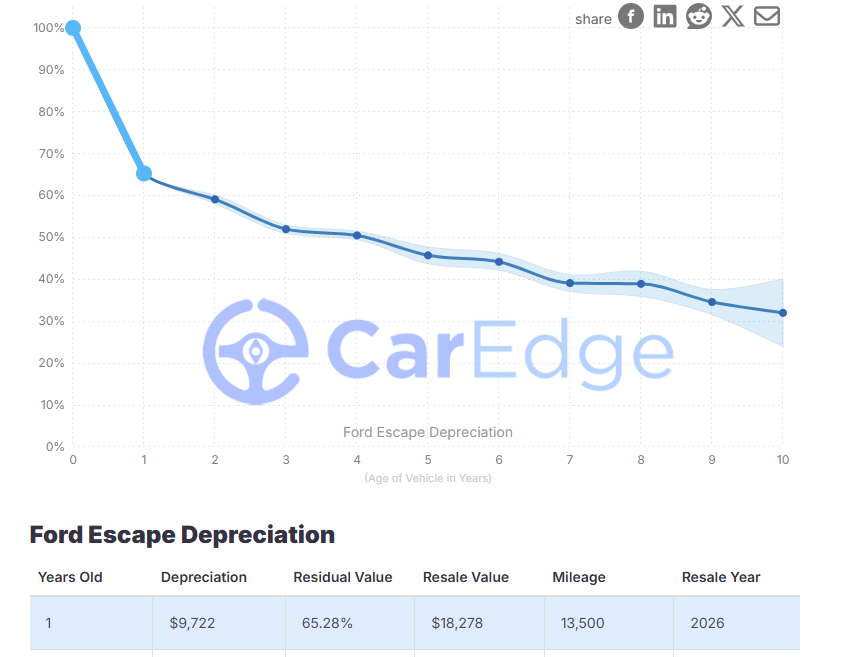

Take the Ford Escape, a $28,000 vehicle that loses roughly 35% of its value within a year, about $9,000 in depreciation. If financed with a typical car loan, the borrower would still owe around $22,000 after one year, meaning they’re already $3,000 underwater. That kind of negative equity becomes especially painful when budgets tighten

The Macro Picture

The auto industry touches nearly every corner of the economy: consumer credit, industrial production, durable goods spending, and local employment. Rising delinquencies and tightening credit are already squeezing lenders. If the cycle turns here first, it could be an early signal that the broader consumer-driven expansion is running out of road.

I’ve written before about the “K-shaped” economy, where growth looks strong on the surface but is increasingly uneven underneath. The strain in auto lending is another symptom of that divide. It’s the middle- and lower-income households, those most sensitive to borrowing costs, who are feeling the pressure first.

Cracks in auto credit might not mark the start of a full-blown crisis, but they rarely appear in isolation. The auto sector sits at the fault line of the U.S. economy, where household leverage, production, and credit all converge. With stress building here, it could be foreshadowing the end of the easy-money phase of the credit cycle. The question now isn’t whether these cracks exist, but how far they’ll spread as higher rates and tighter liquidity test the durability of the consumer engine that’s kept growth running.

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or economic advice. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any affiliated organizations or employers.

While efforts are made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, no guarantee is given regarding its completeness, reliability, or suitability for any particular purpose. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments carry risk, and the value of investments may go down as well as up. The author is not liable for any losses or damages arising from the use of this content.

By subscribing to and reading this newsletter, you acknowledge and agree to this disclaimer.