The Tech Giants Are No Longer Asset-Light Businesses

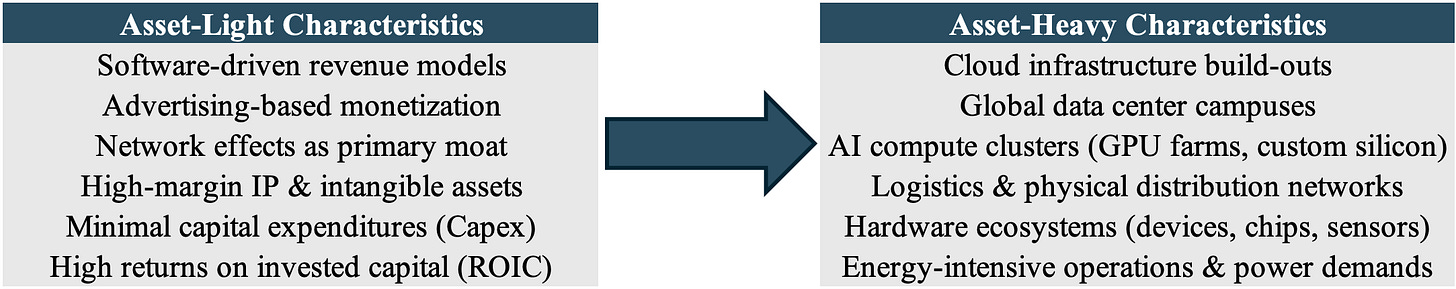

Since the start of tech supremacy, the most attractive feature was their high-growth, asset-light business models. With trillions projected to be spent on infrastructure, that is no longer the case.

The key to a company’s valuation is the price multiple assigned to some form of economic value. The most common measures are earnings, cash flows, revenue/sales, or tangible book value. In short, a company is valued based on the price someone is willing to pay for the economic output it generates.

Technology companies typically do not have or require many tangible assets on their balance sheets (property, factories, machinery, trucks, etc.) like an industrial or manufacturing business would. Instead, their economics are driven by intangible assets such as code, data, networks, and intellectual property.

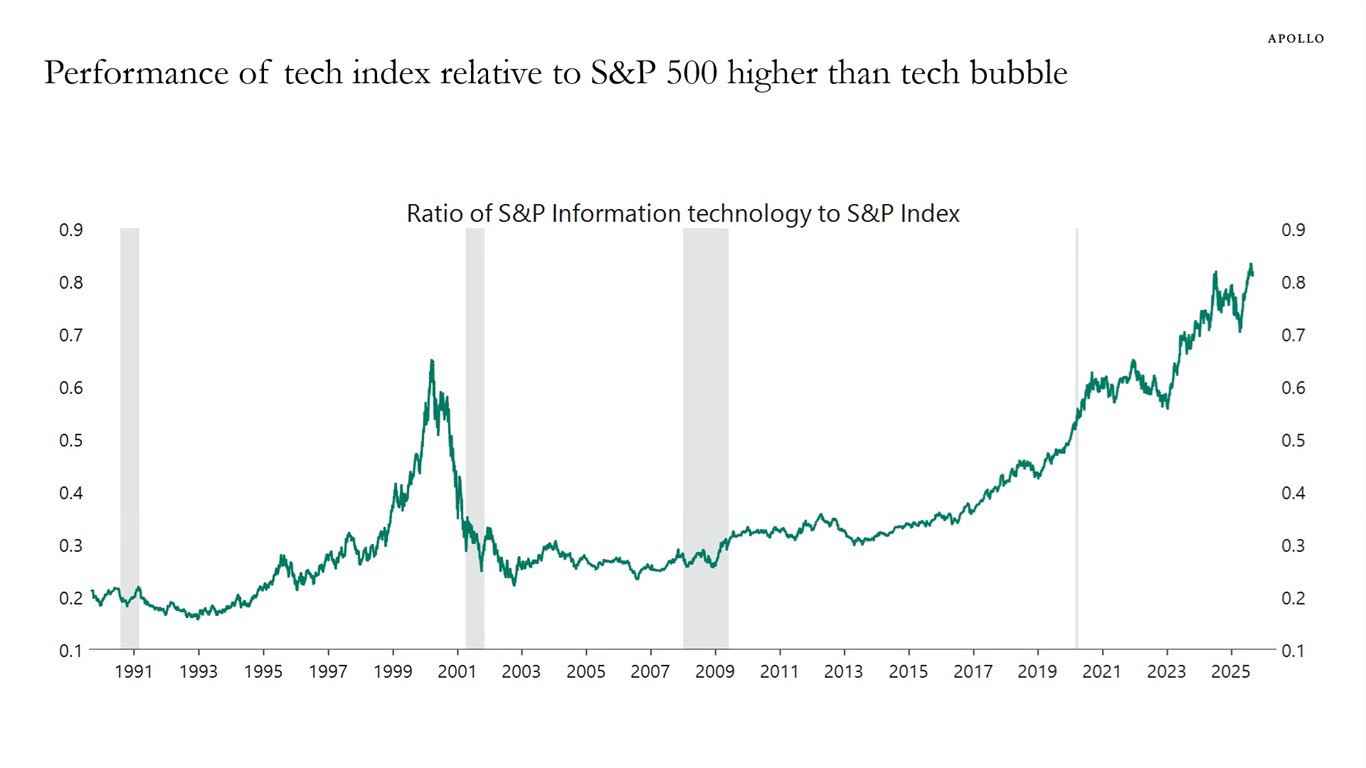

This structural difference has traditionally given tech companies better unit economics, faster scalability, and higher returns on capital, all of which justify higher multiples. Historically, technology firms have commanded 20x–40x earnings multiples, whereas manufacturing and other asset-heavy businesses typically trade at 10x–20x. The wide range largely reflects differences in expected growth, investors pay more for companies that can grow faster.

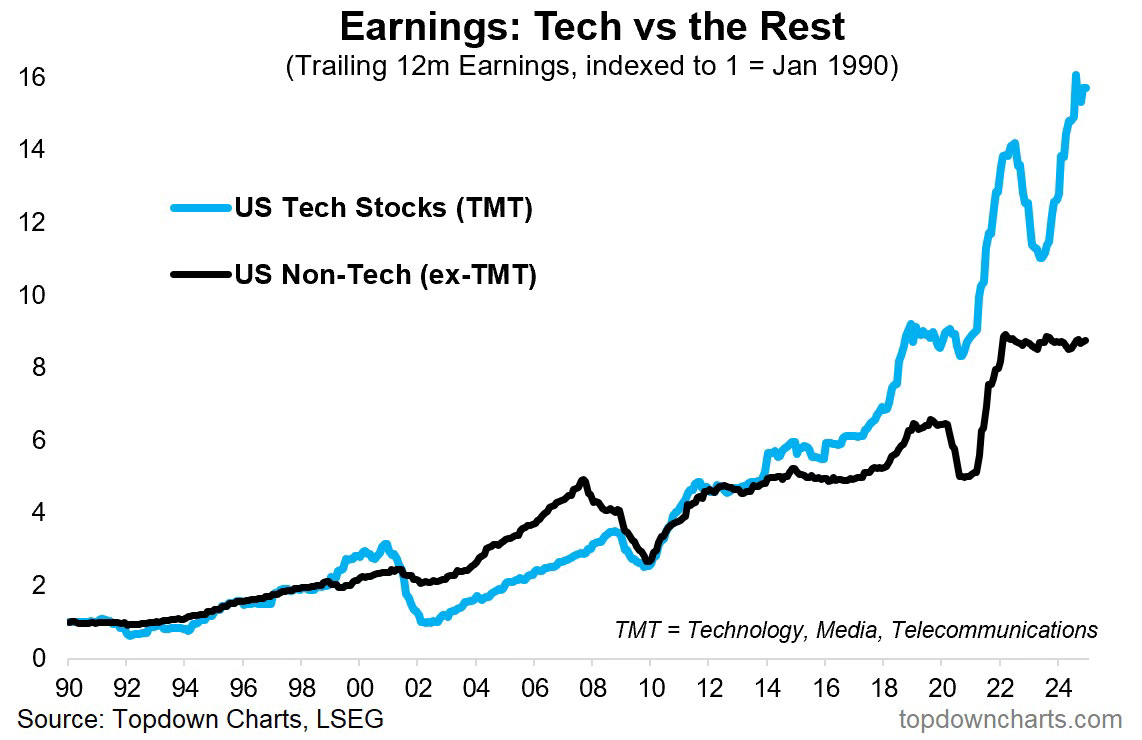

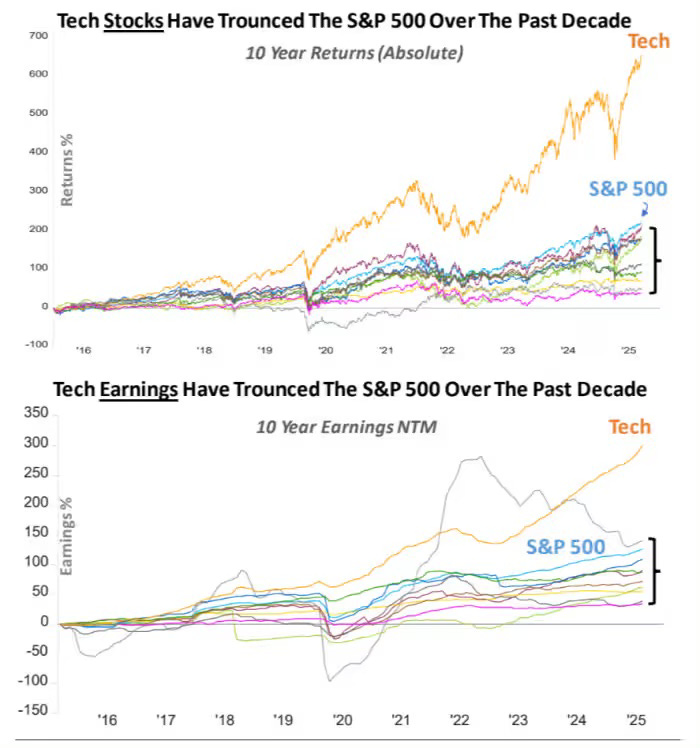

To illustrate how well this asset-light, high-growth model has paid off, the charts below capture it effectively. It also shows how much investors continue to a high premium for these companies.

Big Tech’s Move Toward More Asset-Heavy Models

I’ve discussed previously the significant level of capital expenditures these companies have undertaken and the risks involved. To read more, see here: What If the Massive AI Spend Doesn’t Pay Off?

The figure the clearest way to show how Big Tech’s strategy is shifting is to break down a few of the largest companies one by one. The list below is not exhaustive, but it highlights how major technology firms have evolved into far more capital-intensive businesses in recent years.

Amazon – Warehouses, Logistics & Transportation

This one is a little bit of an older story, as Amazon has been doing this for the last decade, but Amazon, once the poster child for asset-light scalability, have become one of the most capital-intensive companies in the world.

They’ve built hundreds of fulfillment centers, sortation centers, last-mile delivery stations and expanded their transport fleet: planes (Amazon Air), trucks, vans, and maritime logistics.

For inside the warehouses, they’ve invested heavily in robotics and automation.

They have a massive ongoing data center build-out for AWS, one of the largest in the world.

Amazon is now closer to a vertically integrated industrial and infrastructure operator than a software-only company. Its annual capital expenditures rivals the largest global industrial conglomerates.

Microsoft – Data Centers and AI Infrastructure

Microsoft has transitioned from a predominantly software company to a capital-heavy cloud and AI infrastructure powerhouse.

Microsoft Azure (their cloud business) requires enormous global data center deployments (land, buildings, networking gear, cooling).

AI acceleration increased demand for GPU clusters, specialized silicon, fiber networking, and power.

Hardware products (Surface, Xbox) add further manufacturing and inventory complexity, but this is nothing new as they’ve had this business for a while.

The result? Capex has exploded, largely due to cloud and AI infrastructure. Microsoft’s FY 2025 Capex was projected by the company to be $80 billion. Capex now makes up 25% of the companies revenue, more than 10 times what it was a decade ago. Microsoft today looks like a digital utility, with cost structures resembling industrial-scale infrastructure providers.

Alphabet (Google) – Data Centers, Servers, Fiber, and AI Compute

Google was an early adopter of the in-house infrastructure strategy, but the past few years have seen a dramatic acceleration in Capex driven by AI requirements, YouTube scale, and cloud expansion. Some of the major asset-heavy shifts:

Global data center campuses requiring land acquisition, power, and cooling.

Investment in subsea and terrestrial fiber networks, sometimes fully owned.

Custom semiconductors (TPUs), meaning hardware R&D and manufacturing partnerships.

AI compute clusters built for large-scale training and inference.

Meta – AI Training Infrastructure and the Metaverse Hardware Push

Meta historically ran a very asset-light model (ad delivery, software, social apps). This has changed. What’s changed:

Significant investments in AI data centers and GPUs. Not to mention the huge compensation packages they’ve been paying out to poach top talent from its tech rivals (they’ve grabbed senior leaders from Apple, OpenAI, Google and others.)

Massive capex for reality labs, including AR/VR headsets, experimental hardware platforms, sensors, optics, and chip development.

Scaling global infrastructure for Reels, video, encryption, and WhatsApp messaging.

The company that made $80bn in operating income in 2024, is planning to spend $600bn over the next 3 years making Meta one of the largest Capex spenders in the S&P 500, surpassing many industrial companies.

Apple – Vertical Integration & Infrastructure to Support Services

Apple has always been primarily a hardware company (e.g. Apple computer, iPod, iPhone, iPad, MacBooks, etc.), but their primary change in strategy is their move to be vertically integrated. They primarily outsourced most of the manufacturing to partners, but have been making key changes over the couple of years to bring this manufacturing in-house.

Key asset-heavy moves:

They moved more chip design in-house (kicking Intel to the curb), requiring massive long-term investments in silicon R&D and physical testing facilities.

They’ve been building out data center infrastructure for iCloud, Apple TV+, Apple Music, and recently (famously behind everyone else) their AI-related workloads.

Apple’s model has become more capital-intensive as it builds out broader ecosystems and services that require physical infrastructure.

The Valuation Implication

Typically, as a business becomes more asset-heavy, its marginal returns on capital decline. Physical assets require massive, continuous capital expenditures leading to higher depreciation, tighter margins, and the need to reinvest just to maintain capacity. This dilutes overall returns compared with asset-light models, which can scale with far less incremental capital. As a result, valuation multiples naturally compress toward those of industrial, telecom, or infrastructure companies.

However, Big Tech is making these investments because it believes the potential returns from AI leadership will be extraordinary. Whether this is a race to the top or a race to the bottom* remains unclear.

Time will tell whether this historic level of capital spending produces meaningful profits or becomes one of the most expensive capital allocation mistakes in corporate history.

*In brief, the downside scenario (the “race to the bottom”) is as follows:

Each company is forced to outspend rivals to try and achieve AI leadership,

Capex escalates beyond what is rational (if it hasn’t already),

Returns on those investments compress sharply,

And the industry collectively drives itself into poor economics despite chasing growth

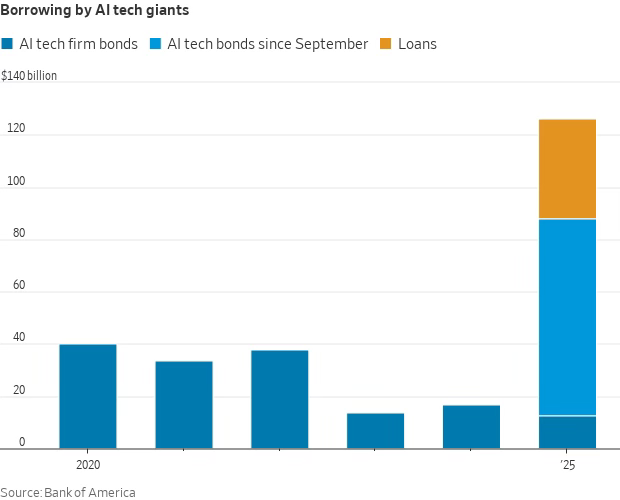

By the way, they’ve also been borrowing heavily to make these investments.

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or economic advice. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any affiliated organizations or employers.

While efforts are made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, no guarantee is given regarding its completeness, reliability, or suitability for any particular purpose. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments carry risk, and the value of investments may go down as well as up. The author is not liable for any losses or damages arising from the use of this content.

By subscribing to and reading this newsletter, you acknowledge and agree to this disclaimer.

This capital allocation paradox is the most underappreciated risk in tech right now. What made these companies dominant was their ability to scale without proportional capital, but the AI infrastructure arms race is forcing them into a completely different economic model. The irony is that chasing AI leadership might actualy compress the exact valuation premiums that justified their market caps in the first place. If returns on this capex don't materialize, we're looking at one of the largest misallocations in modern corporate histry.